The God of Chance: The Legend of Yi Koh Hong, and Tales of The Ang-Yi Secret Societies of Thailand

The morning sun lights up Sampeng Market.

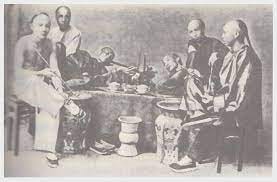

A dreamy twirl of smoke rises from an opium pipe made of bamboo. Three men are on the nod in a shophouse tucked away on a nameless soi just off the main drag. The poppy’s gift laid out before them on a burlap mat. The morning sun does not reach here.

Next door is a pawnshop on the ground floor ran by a family who speaks not a lick of Thai. The mother swaddles a newborn hungry for milk. The father examines a bar of jade inlaid with silver. He’ll underbid the desperate man pawning it.

Upstairs is a gambling den, hong, where a dozen men gather around a fantan table — an ancient Chinese game of chance — littered with porcelain betting tokens: the only currency besides silver that matters here.

Their bets are calculated as they smoke rolled tobacco and silently work out their losses. They haven’t left their spots since the night before, their eyes weary, but the game rolls on.

Outside a hunched man wearing a coolie hat and dirt-caked trousers hawks steamed buns, dried fish, and Chinese puppets. He rents the wooden cart he draws behind him, eking out enough profit to fill his belly — with nothing left for poppy or porcelain tokens of chance.

Other men have different fortune.

One man walks the dusty streets of Bangkok’s Chinatown as a legend — honored by two Siamese Kings, blessed by the Fates, bonded to The Heaven and Earth Society as its leader.

He is worshipped to this day by gamblers, his face on amulets throughout Thailand. His legend is such that these same amulets have been banned by casinos in Macau and Cambodia to this very day.

His legacy is cemented as a benefactor to the land of Siam. He’s one founder of the Poh Teck Tung Foundation, which has worked selflessly for a century to help those in need, in times of tragedy and death, no matter their race or creed. He gave everything he had to Thailand.

He was in command of a criminal secret society, and his former estate now a police station in Bangkok, with a shrine dedicated to him on its roof.

A man that some know and many do not.

This is the story of Yi Koh Hong.

Note: If you’re reading this story and you haven’t subscribed to this newsletter, please do below. It’s free. There’s no spam — only curiosities and histories of Thailand and Asia.

Second note: if you received this as an email newsletter, you have to go to the actual Substack website to read the full version as it’s too long for email. You can read the full story by clicking the red button below:

Origin of the Man Called Yi Koh Hong

A curious flame burns in the land of jade.

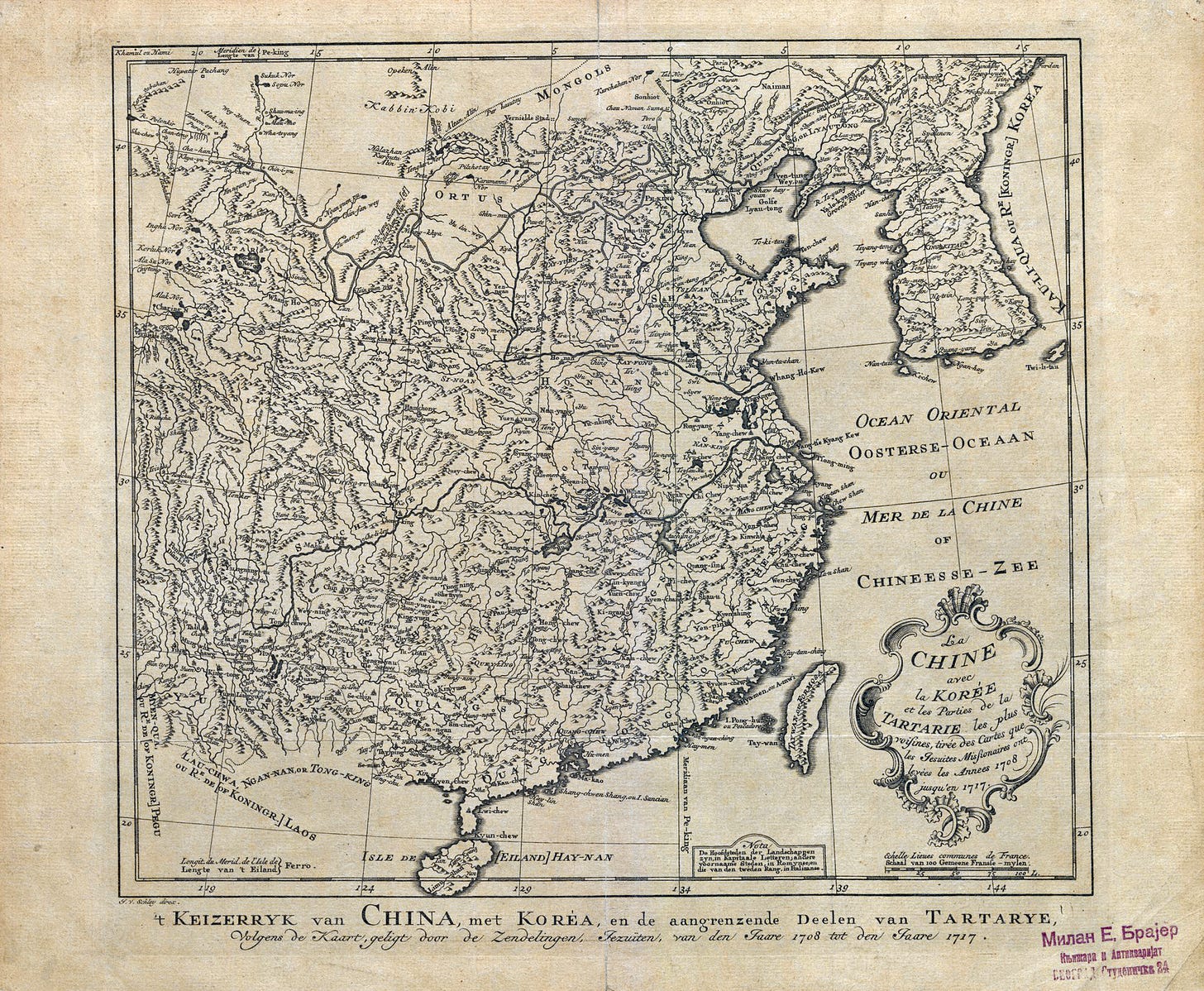

The year is 1851. China is ruled by the despised Manchurian Qing Dynasty and is less than a decade past the First Opium War.

The young Xianfeng Emperor, who ascended to the throne in 1850 at the age of 19, maintains a shaky grip on power. The Taiping Rebellion has kickstarted, fueled by the delirious religious visions of Hong Xiuquan, and will soon become the bloodiest civil war the world has ever seen.

By the time the dust settled, between 20 and 70 million would be dead.

Maritime assaults are common in the vacuum of power. Pirates plague the South China Sea as they raid merchant ships and assault villages.

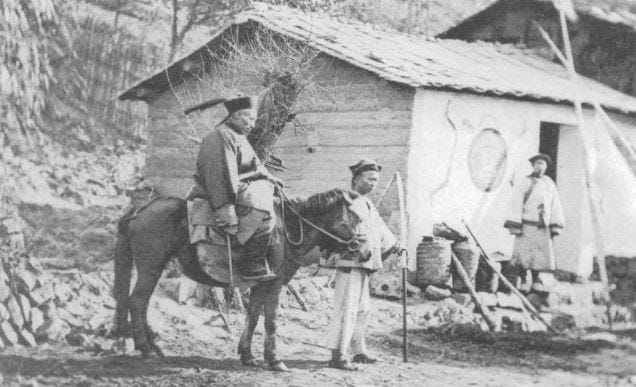

In this shifty terrain of civil war and rebellion in Qing dynasty China, one of the most tumultuous regions was known as Chaoshan, situated in the coastal province of Guangdong, about 300 kilometers up the coast from Hong Kong.

Chaoshan was a small region, one that you'd miss on a map as it had no official borders, but is chock-full of history and personalities larger than life. The history is both bloody and gilded at once, as pirates and merchants, secret societies, rebels, and magnates of industry jostled for power and prestige in the shifting sands of the 19th century.

Tens of thousands emigrated out from this region to settle in Siam, the Malay peninsula, Cambodia, and Vietnam — and further afield in northern California for the Gold Rush.

One of these groups of emigrants are known as the Teochew — and this is the dominant group of Chinese in the South East Asia diaspora.

It's in Chaozhou, a Chaoshan city that lays just inland on the banks of Hanjiang River, in the fateful year 1851, that a boy named Zheng Yifeng (鄭義豐) was born — according to one of his origin myths. Other say he was born in Siam.

There’s one account in the Fengtang Town Chronicles that builds a satisfying origin story.

In this telling, Yifeng’s family was destitute and his father sought work in fields or the sea, whatever would pay first.

Sometimes there was no work, so Yifeng’s father would set off to Siam and do work there. For years he toiled in Bangkok shipyards, sending home just enough for his young son and wife Sheh.

One day, the money stopped coming. There was a letter that came instead: “Zheng Shisheng (鄭詩生) is dead.”

Yifeng’s father passed away in Siam when the boy was seven years old.

The boy and his mother became beggars. A difficult life laid out ahead of them, widowed and poor, they wandered. The young boy became a street hustler with his mother Sheh. Until she found Jieyang Yujiao in Shanghai and remarried — an anchor on the grimy sea.

But the step-father Jieyang abused young Yifeng, and after some time the abuse became too much — so the boy set off to his aunt’s farm to herd cattle, cut hay, and shovel cow-pies.

There’s a bit of legend around the experience Yifeng had in the boonies. One day while setting the cattle out to pasture near Houlong Mountain, young Yifeng met a warlock by the name of Su Banxian — a man who laid his head in a thatched hut on the carved edge of the mountain, skilled in Feng Shui.

Su Banxian was something of a seer. He sat the boy on a tree stump and gave him a look over: strange pupils in the shape of yin-yang, like ancient sages; legs tall and strong; and a mouth like the honest Hou Kuo — all signs that Yifeng would achieve great things in his future.

But the young boy wasn’t convinced. He knew that anything he achieved in his life wouldn’t be because of Fate — rather, his own hard work. Even so, the words of the warlock Su Banxian encouraged the young Yifeng.

The young boy had to go back home, he couldn’t stay with his aunt forever, as they faced their own hardships on the land.

The abuse at home with step-father Jieyang escalated. when Yifeng returned. If it wasn’t the beatings, it was the hunger that hurt. Every day it was hard to fill a bowl of rice, let alone savor meat. The young Yifeng couldn’t tolerate life at home. Not because it was difficult for him, but because he saw how it wore down his mother Sheh. As a boy he couldn’t do much. So he knew that he had to become a man.

The boy Yifeng knew that he could find riches in Siam. It’s where his father went to work and provide for his family, and then to die — leaving his son alone in the cruel world. Yifeng also knew that his mother wouldn’t let him leave to Siam. There was too much pain there. She had already lost her husband to that tropical land in the south, she wouldn’t lose her son there, too.

The budding Yifeng had no money to get to Siam anyway. He could barely fill his stomach with rice. But he knew one man that could help — his uncle Zheng Yuwen, his dead father’s own brother, who owned a pawnshop in the city Chaozhou. The boy snuck out one night from his village home and only looked back once — half-turn while the moon rose full.

Uncle Yuwen heard the boy’s case, but the ask fell on deaf ears. He wouldn’t hand over any silver. And then Yifeng said this: “I will make my father’s name Zheng proud in Bangkok and Chaozhou.”

That name was also his own, so Uncle Yuwen went to the backroom of his pawnshop, pushed back a heavy wooden desk, lifted a floorboard, and took 19 silver dollars from a hidden lode. He handed the coins to his nephew Yifeng and told him to send word when he arrived at Bangkok.

There’s a saying in the Chaozhou tongue that goes, “For the people of Chaozhou, making your fortune far away is the last way.”

If one was to leave, the Chaozhou wisdom was to bring “three treasures” on the journey: sweet, sun-dried rice cakes to sate hunger; a bamboo basket with a lid and handle, for luggage; and a cloth to wash the face, bathe, and cover your lower bits. The cloth could be laid down to the floor to sit and sleep, bundled or made into a bag. The pole useful if attacked by a thug.

These “three treasures” are installed to this day at red-sailed junk ship memorials in China.

Yifeng stocked up for the trip and bought his ticket: the first step to becoming a man.

He then boarded a junk boat at Shantou harbor that set sail to the Chao Phraya.

The passengers stowed away in the hull looked depressed and tired on the long voyage. Except the young man who squatted in the corner of the cramped cabin. Sober, conscious face, contemplating his future. Nobody paid mind to this Yifeng. He looked out over the boundless ocean, keeping his mother and aunt in his mind, and the cousins and friends from his village that he slowly left behind.

“What kind of world will this be,” he must have wondered — thinking of Siam.

When he landed at Bangkok, he found a harbor full of chaos. Hawkers called out selling dried fish, noodles, tickets for a lottery, and a spot at the luckiest fantan table in Sampheng. Yifeng felt invisible in the bustle. Nobody knew who he was, not one of them knew his name.

It was a feeling of simultaneous nothingness and the gut-feeling that he could do anything at all.

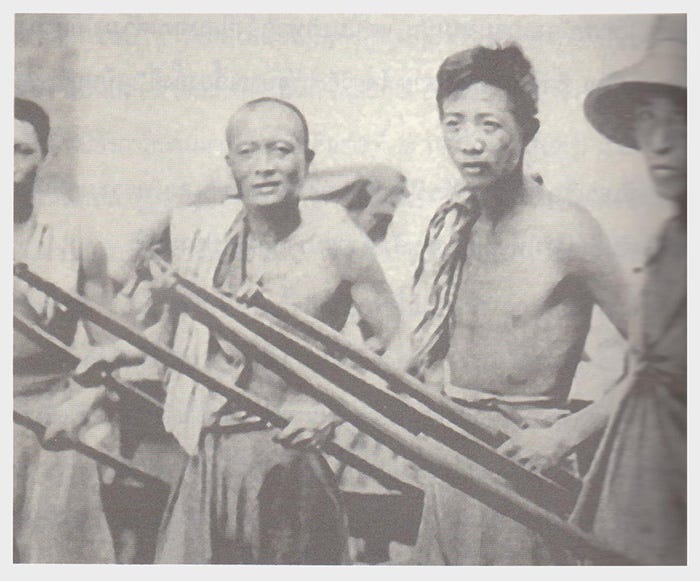

A coolie spotted the lost looking kid and asked if he needed work. Yifeng said yes.

In those first days in Siam, he worked as a carter for a Teochew ran warehouse at the harbor. The workers were a mixed bunch, some Teochew, others Hokkien, and even others still low-born Thais and Burmese. It was a rough crew and they bullied the green hands like Yifeng.

The work was hard and it paid little, but Yifeng kept his chin up and never complained. He stood tall and stood for those under him, and quickly earned a reputation as a “man of justice.”

He caught a lucky break in Bangkok. He got a job at a casino ran by a Teochew man who knew his dead father. This man was called by a few names: Phraya Phakdee Phatakorn (พระยาภักดีภัทรากร), or more popularly — Jiesaw Kongsaw (เจ้าสัวโกงซัว), the Cheating Magnate.

This property was on 1,000 rai and in 1889 King Rama V seized the land, converting the Teochew casino into Siam’s first mental hospital. A strange diversion in this tale, and a thread for another dispatch…

After learning the ways of this strange land, Yi Koh Hong built some courage, and followed a lead to the northern frontiers of the kingdom in Chiang Mai province to work at another casino ran by Jiesaw Kongsaw. He worked as a coolie, then in the forests cutting down trees.

Yifeng pocketed every bia (เบี้ย), solot (โสฬส), and salueng (สลึง) until he had enough to return to Bangkok with a stake — the question was, where to place it?

The only place that made sense — the sois of Sampheng.

He bought a stock of Chinese herbs shipped in from the port Shantou. Then fabrics and clothes that he sold from a wooden cart that he pulled behind him. One day a local thug — a killer, older, but a fellow Teochew — saw how much Yifeng was pulling in from his hustle. So he waited for dusk and jumped the teen and stole his coin.

Yifeng got knocked out, and was left with a bloody face on the dirt street. His cart busted, purse empty. He knew that the only way to survive was to band together with other young men his age who had left Chaoshan for the hustle in Siam.

He recruited easily. And his respect grew.

Other origin stories say that Zheng Yifeng was born in Siam.

One story says that after the First Opium War in 1840, Yifeng’s father took his wife and escaped to Siam on a junk ship. Shisheng opened a fabric shop on Bamrung Mueang Road in Bangkok. Eleven years later in 1851 his son Yifeng was born in Siam.

These are two different origin stories — one rooted in Chaoshan China, the other in Bangkok Siam.

Yifeng claimed himself that he was born in Siam.

His testimony was given to a reporter from the Siam Jing Overseas Chinese Daily (暹京華僑日報), a couple weeks prior to his death, on January 22, 1937. The reporter asked Yifeng about his age, to which he replied, “Eighty-six years old, born in the first year of Emperor Xianfeng’s rule.” The reporter then asked, “When did you come to Siam?” to which Yifeng answered, “I was born in Siam. I returned to Chaoshan for two years when I was 13, came back to Siam at 15, and never returned to China.”

Those two years when he returned to Chaoshan are when he fought in the Taiping Rebellion — which is a bit of his life that is consistently told in any account I found of Yifeng’s life.

Some scholars in China disagree with Yifeng’s own birthplace claim, citing the testimony of one of Yifeng’s many grandsons that his grandfather was born in China.

It’s beyond the scope of this piece, or my interest to be honest, to determine with confidence where Yifeng was really born.

But if you forced me to take one side or the other, I’d say he was born in Siam — but was brought back to Chaoshan to be raised by his mother, while his father worked in Siam. It’s a good mix of the best origin story and Yifeng’s own word. This is just my instinct, a hunch, a hazy guess.

What I’m most interested in is what this man did in his life.

And he did a lot.

His accomplishments and legacy are reflected in the names Zheng Yifeng earned throughout his lifetime:

Zheng Zhiyong (鄭智勇), a name given to Yifeng in 1908 by the anti-Qing revolutionary leader Sun Yat-Sen. They plotted together in Bangkok for the overthrow of the Qing. Zhiyong here means “rich” or “abundant”.

Deputy-Head Phra Anuwat Rajaniyom (รองหัวหมื่น พระอนุวัตน์ราชนิยม), a name and title bestowed by King Rama VI, for his virtues and service to Siam. It was given on June 1st, 1918, and the title was Deputy Head of the Department of Interior.

Hong Techawanit (ฮง เตชะวณิช), a surname bestowed on July 28th, 1918, along with the position of a duty officer. There's a road with this namesake, which is part of King Rama V road, as it terminates in Khwaeng Bang Sue.

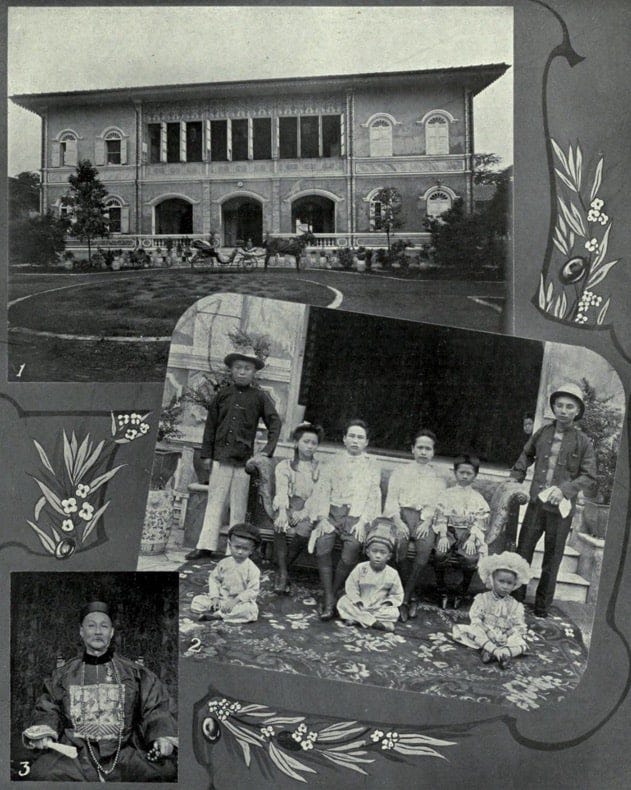

Doctor Ronglu (榮祿大夫, หย่งหลกไต่ฮู), an imperial title that reaches back to the 3rd century Jin Dynasty, where a doctor named Yinqing Ronglu was appointed as an official. Through the Yuan Dynasty and to the Ming Dynasty, the title was given to various officials and ranks. This is the form that we see most often of Yi Koh Hong, on amulets and photos, wearing imperial clothing and hat. Yi Koh Hong earned this title after donating 100,000 taels of silver — 3,700 kilograms of the lunar metal, worth 2.3 million USD today, a truly astounding figure — to a disaster relief fund when his home region of Chaoshan was hit with an earthquake.

And most importantly, the name that carries his legacy to this day: Yi Koh Hong (ยี่กอฮง, 二哥豐 [Ergefeng]) — a name he earned as the “Second Brother”, which was a couched way to say the main leader, as the “Big Brother” (ตั้วเฮีย, tua hiya) title was one he was too humble to take — of the Bangkok chapter of the notorious secret society Tiandihui (The Heaven and Earth Society, 天地會), also known as Hongmen ((洪門, Vast Family) to the Han.

Many know this group now as the Triads (三合会, sahuhuei) — but it meant something more in those years.

The work and legacy of this secret society in those years past is the conceit of my piece here.

I will explore the life of Yi Koh Hong along with the history of the Ang-Yi (อั้งยี่), which was what these Chinese secret societies came to be known as in Thailand. The Ang-Yi is a name that to this day invokes moods of crime, mafia, and conspiracy.

It’s a name even codified into the Thai criminal code, section 209, for those who would wish to conspire in secret groups — with a punishment not to exceed 10 years imprisonment or a fine of 20,000 baht for the chief of such a secret order.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

Without further ado, the early years of Yi Koh Hong — what we know of them, at least.

The Taiping Rebellion and Yi Koh Hong, a Made Man, Returns to Siam

There’s a memoir titled The World of a Tiny Insect written by one Zhang Daye.

He was born in 1854 in the midst of the Taiping Rebellion. His village was destroyed at the age of seven. As a man he reflected on the experiences from the rebellion and put paper to pen with these memories, the way he saw them with young eyes.

The preface to his memoir begins with this line: “From the cry of a tiny insect, one can hear the sound of a vast world.”

And who hears the sound of that little bug?

Is it a man of destiny? A man like Yifeng?

Perhaps — but first, let’s simmer a bit here on this civil war.

For 13 long and bloody years the revolutionary Hong Xiuquan proclaimed himself as God — with Jesus ranked second in his command. It all started when he kicked off the Jintian Uprising on the eleventh day of the first lunar month of 1851: the birthyear of Yi Koh Hong.

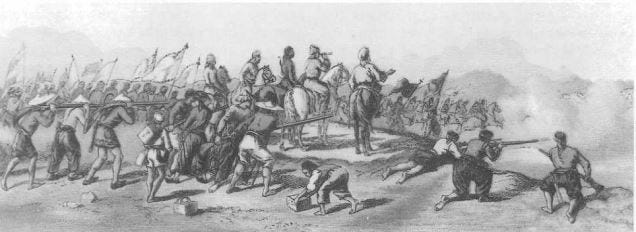

His twenty thousand soldiers and devotees, known as the God Worshipers, took the town of Jintian by force. They overpowered a small legion of Qing soldiers, who suffered roughly 1,000 casualties.

Jintian, a small town located in the modern day southern coastal region of Guanxi, now belonged to Hong Xiuquan. A small victory, but one that would soon become a massive problem for the ruling Qing Dynasty.

This was the start of what we now call the Taiping Rebellion and the establishment of the rogue state, the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom (太平天囯). This rebel kingdom expanded into modern day Jiangxi, Zhejiang, Anhui, and Hubei provinces, with Nanking serving as the capital.

Their stated enemy: the Manchus, no matter if commoner or in the Qing Imperial Palace. They would slaughter Manchus at any opportunity. In the street, in their homes, it didn't matter.

The Manchus were demons in the eyes of the God Worshipers.

The Taiping rebels didn’t fight alone.

Concurrent with the Taiping Rebellion were other rebellions contra the Qing: the Chinese Muslim led Panthay Rebellion in Yunnan; the Dungan revolt in the country's northwest; and the Red Turban Rebellion in coastal Guangdong, which is where Yi Koh Hong likely stayed.

The Qing could squash one fire, one uprising, one provincial rebellion, only to face a greater one smoldering in its ashes.

One example is an uprising led by the Tiandihui, the Heaven and Earth Society, in Guanxi — just northwest of Guangdong. A famine struck the people of this province in 1849 and the Tiandihui, who stacked their lucre in the trade of opium, whores, and piracy, rose up against the Qing.

This skirmish between the secret lodge of the Tiandihui and the Imperial Army left a chink in the armor of the Qing, which the God Worshippers took full advantage of — and was one of a thousand cuts that led to great carnage.

Along with other domestic insurrections, the Taiping rebels recruited foreigners from the West to their cause. This motley crew was never large — as the Taiping was skint to pay them — but as many as 200 were known to have fought in the battles against the Qing on the side of Taiping.

Italians, Irish, Americans, Englishmen — one from that last bunch, a seaman named Savage, lived up to his name: he died while defending an attacking from Imperial forces, and an American called Peacock filled his shoes.

Some westerners became officers in the Taiping army — a Sardinian officer named Moreno earned the rank of lieutenant colonel (leu-shuai), leading a battalion of men. A yank called Henry Burgevine commanded the whole Ever Victorious Army, with a corpse of 1,000 men, and was made a general.

A pithy resource I found on this war is titled The Taiping Rebellion 1851-66 by Ian Heath — worth a read if you can track it down, and in his bibliography he lists some of the first tomes that were penned on this war. It’s a subject I may return to in a dispatch down the line.

Fast forward to 1864 and the fighting has reached a crescendo. In a climactic clash in the Third Battle of Nanking the Taiping Kingdom came to a decisive end.

The 13 years of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom saw immense bloodshed. Some calculate the number at 20 million casualties. Others 70 million — some 600 cities had changed hands in the war, some districts losing 40-80 percent of their population, death stacked up from the clashes between Qing soldiers and the God Worshipers loyal to Hong.

The Third Battle of Nanking ended the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom with total destruction. Over a period of four months Qing soldiers slaughtered 100,000 of Taiping’s best, pillaged the city of Nanking, stole its young women off to gang rape, burned palaces and homes with wanton abandon.

We don’t know where Yi Koh Hong was in the midst of this chaos. He was only 13 years old, and it was sometime around this age that he left the hustle on Bangkok’s streets to stay with his uncle in Chaozhou. He had to make a life in Siam, but that was all worthless if his people fell at the hand of the Qing.

He doesn’t pop up in any historical accounts for another couple years.

Though this last stand at Nanking left the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom destroyed and Hong’s God Followers scattered to dark and unfavorable winds, battles continued for the better part of the next decade between rebel and Qing forces.

One of these battles was set in Dabu in Guangdong province, just north of Chaozhou, in February of 1866.

This was Yi Koh Hong’s stomping ground — and it was his time to rise to a historical event. He joined the battle, taking up arms with the Tiandihui, the legendary secret order, alongside a motley crew of God’s Followers both united against the Qing legions. After this battle he is initiated into the Tiandihui. Because of valor or for participation, it didn’t matter — he was in.

Yi Koh Hong had earned his stripes as a made-man at the age of 16.

Yi Koh Hong had respect. He got it by putting his neck on the line in a battle that has a legendary status in Chinese history. And after the dust settled he returned to Siam.

There were many other Teochew Chinese from the Chaoshan region who stayed in Bangkok.

In fact, King Rama I’s mother was at least part Chinese — and some speculate that she was Teochew. But he reigned long before Yi Koh Hong was even an idea.

By the time our Hong arrived back to Siam, it was King Rama V who would soon take the throne. Coronated in 1868, he ruled Siam and brought the Kingdom into the modern age — aided in part by a savvy Yi Koh Hong and his business ventures in the shipping trade, opium dens, and gambling.

Introducing the Ang-Yi, or the Chinese Secret Societies of Siam

History is not one long continuous string that you can pick up and follow to a certain end.

It’s a tangled mess, a ball of endless knots. When I start to pick at and unravel bits of the history of Yi Koh Hong, I tease out and solve one knot only to find ten more — new places to focus my attention for awhile — and before I know it, I’ve forgotten the initial object of my inquiry.

Nangklao, or King Rama III (พระบาทสมเด็จพระนั่งเกล้าเจ้าอยู่หัว), came to rule Siam after his elder brother, Rama II, passed suddenly. The ascension of Rama III was not without rumor of usurpation — I suppose as any sudden death of a monarch sees — and he reigned during a long period of transformation in the region, where antagonistic kingdoms in Burma, Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam were stifled and left to smolder under colonial rule, and Western powers came to negotiate with the Kingdom of Siam.

His reign lasted from 1824 to 1851 — that year 1851 again, the year of Yi Koh Hong’s birth.

The rule of Rama III saw an influx of Chinese into Siam. Many settled in the alluvial plains of Bangkok, but not exclusively. Many of the immigrants from China labored in the Phuket tin mines and throughout the far-flung southern provinces in sea-side towns all the way down to Malay.

They formed labor gangs, factions that were not united under a common Chinese banner, but battled each other for opportunity in the foreign and sweltering land of Siam.

These labor gangs were the first Ang-Yi, or Chinese secret societies in Thailand.

And they weren’t always peaceful.

The Ang-Yi is a bastardized word, coming from a south China vernacular known as Minnanhua (閩南話), used by the Hokkien and Teochew. It's not Mandarin or Han, as they call secret societies Hongmen (洪門) — the vast family. The Triads (三合会) are another name for this group that has been used for centuries — the etymology of this word is murky and varied, and it is one that I will explore in future dispatches.

The etymology of the word Ang-Yi is murkier still. Some say it's from the way the word Hongzhi (紅字, "scarlet letter") is said in the Minnanhua dialect.

Others say the etymology lies in the word Hongzhi (洪子), meaning son of the Hongwu Emperor — significant in Chinese history because he liberated the Han from the thumb of Mongolian Yuan dynasty rule, established the Han-led Ming dynasty, which was later overthrown by the Manchu and establishing the Qing.

This battle between Han and invader for the Imperial Court resonates throughout Chinese history.

This thread of taking back the land from the Mongols, having autonomous Han rule under the Ming, and later losing sovereignty again under the Manchu Qing, leads us to the secret society connection in China, as they were often the ones behind plots to bring down empires as detailed in the previous section.

You see, I’ve found another knot. A big one.

If I pick at this one, there will be 10,000 more.

Bloody and Hoary Origins of These Secret Societies

It would be amiss for me to ignore the bloody and horary origins of the Ang-Yi and the secret lodges in China which precede it. The lore of China always makes reference to past historical and mythological events, which are the core to understanding other ages in the Middle Kingdom’s history.

I will unravel one of the larger knots of our story now, so that a fuller understanding of the Ang-Yi and Yi Koh Hong may blossom.

W. A. Pickering wrote about the Ang-Yi and Chinese secret societies in the July 1878 volume Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society.

It's one of the first and most thorough accounts in the English language of these societies. Pickering had a special position to write about them, as he served as the first Protector of Singapore who was fluent in Mandarin, Cantonese, Hakka, Hokkien, and Teochew. His insights into the Chinese secret societies of South East Asia are invaluable. He won his knowledge through direct acquaintance with members and leaders of these secret lodges.

Like most good origin stories, the start of these societies is in strife.

The year is 1664 and there are threats to the Qing Empire from all sides.

The Dutch have returned to Batavia, modern day Jakarta and home base of the Dutch-East India Company, as their alliance with the Qing faltered. But the Dutch still assist the Qing's imperial goals: a failed attempt to invade the Kingdom of Tunging on Taiwan; and squashing the ember remnants of Ming loyalists.

But our story focuses on the drama unfolding in the western lands with the Oriats — who were known as the Elueths in a past day, a group of Mongolians in the western reaches of Siberia and Xinjiang — and their invasion of the boundary regions of the Middle Kingdom.

The Kangxi Emperor, only ten year’s old, bright-eyed with cheeks scarred from smallpox, was forced to play a strong hand. He sent large armies to subdue the barbarian threats in the west, but each imperial legion was defeated. The young emperor’s shoulders carried a heavy burden. A share of his land in the western outskirts of Imperial China was ceded to the Mongolian hordes.

The young Kangxi consulted the wizened noblemen of his kingdom about the threat and loss. The advice that fell on his soft ears: send another army and vanquish the Mongols once and for all.

But not many would take up this fight.

Even after giving hawkish advice to the Emperor, the noblemen admitted that they could not raise another army. Instead, they advised that Kangxi issue an edict, that whoever could subdue the Elueths — no matter their race, creed, or status — would receive 10,000 taels (375,000 grams) of gold and lord over 10,000 families.

Certainly with an offer like this a mercenary force would emerge and seize victory and bounty.

The edict was issued and notice was nailed throughout the Empire with haste. Every village, town, and city on the map was notified.

It's said that there was "No place under Heaven which the edict did not reach."

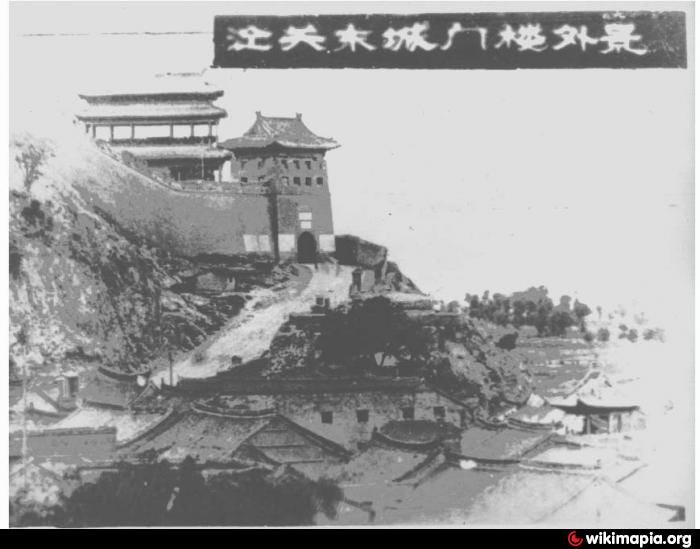

Tucked in a mountain of Guilin, in the district of Tean Leng in old Hakkian land, of modern day Guanxi, there was a monastery called Shaolin Si (少林寺).

This was the Southern Shaolin Temple of legend — a place disputed by historians as ever having existed.

A land that Qing scholar Gu Yanwu describes as “leaning on the mountains and resting in the sea…” — a land full of foreign silver that flows through its ports, where men grow cotton and women spin silk, iron is wrought, and salt is mined.

The legend says that this temple had 128 monks living there, who when they heard of the imperial edict to defeat the western Tartars, at once stood up to the offer.

They were summoned by an Imperial Commissioner who asked them if they truly dared to vanquish the barbarians, to which the monks replied in unison, "To this task there is no doubt, talents and ability dwell among the monks as the old saying goes, and we will conquer the Elueths without help from the Imperial legion."

The monks were ordered to prepare their belongings for a trip to the Forbidden Palace to hold court with the Emperor Kangxi in the Imperial City of Beijing.

The Emperor had the monks brought before him, and seeing their strength and courage, was pleased. He handed the abbot an ancient ceremonial sword of jade and steel with engraved characters for the "sun and mountain" in a triangular form.

Blessed by the Kangxi Emperor, and with a single-pointed mind on the task of vanquishing the Tartars, the monks set forth the next day.

One wonders if the Tang Dynasty poem from centuries before echoed in their heads:

Thinking only of their vows to crush the Tartars,

On the desert, clad in sable and silk, 5000 of them fell —

But arisen from their crumbling bones on the banks of the river at the border,

Dreams of them enter, like men alive, into rooms where their loves lie sleeping.

Wen Tingyun (温庭筠), 9th century, Tang Dynasty

One day I will write more about this poet Wen Tingyun — a monger, a saint, a pauper.

Back to Shaanxi for now…

This was not the first, or last, rodeo in those western lands — many had spilled blood in the desolation staving off the Mongols.

Stories of this land even filter down to the modern West.

I recently listened to an interview with Gore Vidal, where he related a quote from Brooks Adams, great-grandson of the second American President John Adams, "He who controls Shanxi province controls the Earth," as it was a land loaded with minerals and coal. Brooks Adams was an empire builder himself, which Vidal details, and soon enough American troops were on the Great Wall of China and occupying Shanghai. History doesn't repeat but it does rhyme.

This western edge of the Middle Kingdom has always been an apple in the eye of invaders.

It was a 1,000 kilometer trek southwest from Imperial Beijing to these border regions. A treacherous trek across rice fields, backwater villages, and mountain passes. After a fortnight on foot the band of 128 monks reached the frontier town of Tongguan, in modern day Shaanxi province, and met with local generals who had been fighting off the Mongolians. One general handed the abbot of the warrior monks a map and inked the spots that housed barbarian camps.

This is where they would attack.

That night, the monks sipped hot tea prepared by fair Tongguan maidens, and contemplated the line of attack.

It’s worthy to pause for a moment and consider why these Shaolin monks chose to take up the Emperor Kangxi’s edict, which promised a mountain of gold and power, if they had given up the bonds of the world and retreated to their mountain temple?

And further, what does all of this have do with our Yi Koh Hong?

The only answer to the first question that I could land on, after a fair deal of contemplation, was that the Middle Kingdom was under an existential threat — and the Shaolin monks didn’t want the gold, but rather to protect the empire.

This was their solemn duty.

As for Yi Koh Hong, who later became a leader in a secret society that was founded by these very monks, we can assume the same. Did he get rich in Siam? Yes, he was wealthy and honored by two Siamese Kings. But his motivation was deeper, to further the existence of the Middle Kingdom itself — and to overthrow the Qing, a topic we will explore later in the account of his life and deeds.

Night fell on Tongguan and the Sandman took the Shaolin minds to his realm. The next morning the monks woke and set off to where the general marked on the map. In short order they encountered the Mongolian chieftain Phen Leng Thien, mounted on a horse. He was tall, burly, and mean, his face covered with beard, his furs and leathers caked in blood and mud. This was a man raised to battle.

He was a killer. His eyes were set on reliving the destruction his great ancestor Genghis Khan — descended from the blue-eyed wolf (Borte Chino) and the doe (Qo'ai Maral) — leveled on the Middle Kingdom.

The Tartar warlord looked out and saw nothing but a crowd of bald-headed monks, laughed, and said, "You monks are obedient to the Emperor. If you really are withdrawn from this world, why don't you keep your sacred vows? How dare you challenge me."

The abbot replied, "Barbarian dog! The Chinese have nothing in common with you Tartars, any more than with wild pigs in the wood. Will you attack us blindly and meet your own end?"

The Mongol chieftain quipped back, "Won't somebody kill this monk?" And at that, one of his soldiers charged the abbot on horseback with sword raised high, ready to fell the abbot's bald head.

Just as the long sword was to strike the abbot's neck, another monk by the name of Choatek Tiong appeared like a flash of lightning. With knives in each hand, he jumped to slash the barbarian horseman, and cut the enemy thirty times. His blood soaked into the mud of the Mongolian camp.

Before that blood could dry a skirmish between the horde and the monks ensued. After seeing the strength and heavenly luck of the Mongol chieftain during battle, the abbot recalled his monks to retreat, much to their disappointment. They were ready to squash the barbarian forces completely.

The abbot explained that night that if they were to defeat the General Phen Leng Thien, then it would have to be done with strategy.

His plan was clever and destructive in equal measure.

A ravine cut through the Hutek Valley, and that's where the abbot planned to set an ambush.

The strategy was simple: 30 monks would lie in wait on the left flank of the valley, and 20 others on the right. Each monk would have wood, straw, sulphur, gunpowder and other explosives. They would wait for the Mongolian chieftain and his horde to enter the valley and then attack.

It didn't take much to lure the chieftain into the ambush. The morning following the first skirmish, one of the elder Shaolin monks barked some curses at the Mongolian warlord and this was enough to enrage him and send his horde into the ravine.

Once the full force of the Tartars was in sight, the two groups of monks armed with firepower and mines let loose their arsenal. It's said that, "Heaven and earth were obscured by the blaze and smoke" and in this one attack more than 30,000 soldiers and 1,000 officers of the Tartar army were annihilated.

The chieftain Phen Leng Thien escaped with his horse and fled into the mountains, which were so rugged that he abandoned his trusted steed — the familiar of a Mongolian warrior — and escaped on foot like a common soldier.

The abbot foresaw the chieftain's escape, and had men waiting along the path. When they saw Phen Leng Thien approach, they let loose fiery arrows, which finally ended the brave and vicious Mongolian chieftain's life. He had met his final fate and his campaign to destroy the Middle Kingdom had perished alongside him.

Imagine the victory party held that night in the far-flung borderland of Tongguan. Dance, women, wine, any earthly delight would've been on offer after the hell-dogs on horses were defeated — but did the Shaolin monks partake?

We’re only left to imagine.

But imagine further still the honor and celebration when the monks and the Imperial Army reached the Emperor's court.

The Emperor addressed the 128 monks, who all survived, "These invincible heroes, your courage and valor have never been equaled."

The Emperor bestowed titles of nobility to each soldier in the Imperial Army that fought alongside the monks, but the monks excluded themselves from these honors.

The abbot told the Emperor, "We have retired from the world, and don't need these worldly gains. Allow us to return to our Shaolin monastery, so that we may live out our lives in virtue. This is the only kindness we ask of your Majesty."

The Emperor conceded this simple demand but did gift the monks with 10,000 taels of gold — or 400 kilograms of the solar metal, a lode today that would be worth $20 million.

Some of the newly minted nobles of the Imperial Army pledged loyalty to Shaolin monks, as they saw their bravery and heroism on the battlefield. One of the noble generals was named Kun Tat, who swore to protect the Shaolin at any cost.

When great honors are given and piles of gold are handed out, you can be sure that snakes and rats hear about it.

Two of these bitter creatures of the court, by the name of Kien Chiu and Tan Hiong, were not pleased that the Emperor blessed the monks and also their own court rivals — their main rival being Kun Tat, who they had as enemy long before the war and victory in the western lands. The two devised a conspiracy, one that didn't exist in truth, but that would deceive the Emperor into supporting their plot for revenge.

They snuck in a quiet moment of the court and laid the conspiratorial plot at the feet of the Emperor. The conceit? That the 128 Shaolin monks were so strong, such cunning warriors, that if they turned on the Emperor at any point, his rule would be in jeopardy. Further, they had heard whispers that the newly minted noble, Kun Tat, had pledged full loyalty to the Shaolin over the Emperor.

The young Emperor Kangxi, just a boy of 10 years, bought the story hook, line, and sinker. He asked what could be done about the Shaolin threat and the traitor Kun Tat.

The two snakes had an answer at the ready: they would go to the Shaolin monastery bringing gifts of wine for the New Year's feast. Hidden in the jugs of wine would be a taste of the monk's own medicine: explosives, sulphur, gunpowder, which would be used to blow up their sacred retreat in the southern mountains.

At the same time, an assassin would be sent to Kun Tat, carrying a gift of a red silk scarf, which would be used to strangle the noble general. This plot was successful and Kun Tat was murdered, leaving his family plunged in grief.

For the task of squashing the Shaolin, the Emperor gave the two rats, Kien Chiu and Tan Hiong, troops and the weapons they asked for. After a long journey south, the two rats searched desperately for the sacred Shaolin temple, but found nothing. Not until they met a carter by the name of Ji Hok, who knew of the Shaolin, and showed the two rats the way.

They scaled the misty mountain steps and entered the Shaolin monastery. Bearing gifts and smiling countenance, the group were welcomed in by the monks. The Qing Imperial troops that had followed the two rats stayed hidden in the surrounding mountains. The two rats presented the monks with festival wine, which the Shaolin order was grateful to receive, and they all celebrated together. But as the monks poured the festival wine, an odor arose and caused a suspicion. This wasn't just wine in those jugs.

The abbot took a sword, said to have had magical properties, which was gifted to the order by the founder of the Shaolin himself, and dipped it into a jug of wine. A strange vapor rose from the jar and terrified everybody there. The plot was exposed.

The abbot immediately raised his sword and cut straight through the neck of Kien Chiu, whose head fell with a thud on the sacred Shaolin grounds.

But it was too late. Before the monks could mop the blood of the duplicitous Kien Chiu, there was a great commotion outside. The sky was lit up with ten thousand flames. The attack on the legendary Shaolin temple in the south was devastating.

The flames were everywhere and there was no route to escape. This blaze burned for two hours and there's no way of knowing how many died as the sacred temple burned.

Eighteen of the monks lived. They carried the seal of the Shaolin and the magic sword of its founder and threw themselves at the feet of their sacred Buddha. As the fires engulfed every mountain and room around them, and the black smoke billowed in to seal their doom, a celestial spirit appeared. Using the powers of the Buddha (siddhis, सिद्धि), the celestial spirit opened a golden path out from the monastery, through the flames, and to safety.

The eighteen monks made their escape.

They trekked for miles, mourning the loss of their sanctuary and the deaths of their brothers in the order, until they spotted one Ji Hok in the distance. He was the carter who had brought the two rats to the temple, and now he was escorting Imperial troops through the mountain pass.

The monks made an easy decision. They would take revenge for the deceit and betrayal of Ji Hok and kill him, and after decide what to do next. There was only one problem, of course: to get the betrayer Ji Hok, the monks would have to fight a large retinue of Qing soldiers. This did not dissuade them. The monks stormed into the crowd of soldiers, dragged Ji Hok out, slit his throat and bled him dry to his death.

Revenge was complete and now the monks had sparked the wrath of Qing soldiers, who were fresh and battle-ready. The monks lost thirteen more of their brethren to the Qing sword, and five of the survivors escaped, their names: Cai Dezhong (蔡德忠), Fang Dahong (方大洪), Ma Chaoxing (馬超興), Hu Dedi (胡德帝), and Li Shikai (李式開).

A side note here to give context on how legendary these monks were.

There is one account of the incident at the Southern Shaolin Temple that says one of the surviving monks was none other than Bak Mei (白眉) — the legend from Kill Bill vol. 2!

The five monks found refuge at a temple on Black Dragon Mountain. They were able to hide in secret from Imperial forces, who were in search for them, for some time.

One day, a monk took a stroll to a nearby creek. On the muddy banks he found a jade censer in the shape of a triangle. On the bottom was an inscription: "Hoan Qing, Hok Beng" (in the Hokkien dialect) ["Fan qing, fu ming (反淸復明)" in Han, which means roughly, "Drive out the Qing, restore the native Ming line"].

This saying was raised on banners of rebellion against the Qing since, and it became the ideological lodestone of these secret lodges.

The monk was soon joined by the other four and they celebrated together, knowing that this was a sign from Heaven. They felt a connection to the ancients Liu-pi, Chang-fi, and Kwan-yu La, who lived 1500 years before, and who had founded another ancestral secret order.

The monks were soon surrounded and there was no path to escape. But the monks were protected by forces not of this world. A woman named Koeh appeared wielding a celestial sword with the sayings "Two dragons disputing for a pearl" and "Overthrow the Qing, restore the Ming" on its hilt. She struck down the Qing forces and rescued the monks from certain death.

Who was this lady Koeh? She was the very wife of the murdered noble general Kun Tat, the man who had pledged his support to the Shaolin monks at the Imperial Court.

The monks rested at her home for a couple of nights before returning to their secret hideout on Black Dragon Mountain.

Not long after these strange events, a Taoist hermit by the name of Kin Lam showed up at the temple on Black Dragon. He wanted to meet the monks, who he had heard rumors about from travelers. But the monks had since fled Black Dragon Mountain as they knew the Qing troops were hot on their trail. They now stayed at Dragon and Tiger Mountain with hundreds of rebels who also despised the Qing dynasty.

The Taoist hermit spent months trying to find the monks, and after a great deal of searching, was successful. He pledged his support to the cause of overthrowing the Qing.

The rebel soldiers, monks, and the Taoist hermit were united in their mission. An auspicious day was divined by the hermit to begin their official order, and in the Honghua Ting ("Vast Red Flower Pavilion"), on the 25th day of the 7th lunar month, the men mixed their blood and swore an oath to their joint cause.

The five monks were appointed as generals of the order and the Taoist hermit Kin Lam was the Commander in Chief. The order was called as Tiandihui (天地會), or the Heaven and Earth Society.

It would be 250 years later when Yi Koh Hong would lead the lodge of this order in Siam.

A very strange anecdote follows the formation of the order. The following day after the initiation took place, the men set foot towards Banhun Mountain. On this mountain they found a man by the name of Banhun Lung.

Banhun Lung lived alone as a hermit on this mountain. He had given up on this world, his home, and his three sons, because just months before he murdered another man. Solitude was his penance.

It's said that Banhun Lung stood nine feet tall — a likely exaggeration, but a noteworthy anomaly: was he a giant of some lost or mythical race, or just a tall westerner? — with a face big as a sink, which was covered with a thick red beard. He always carried with him a pair of dragon maces and his strength was greater than any man the monks or rebel soldiers had ever seen.

After hearing the goals of the newly founded order, Banhun Lung joined them, inspired by their quest for righteousness and to avenge the imperial oppression. The monks and Taoist hermit were glad to welcome the red-bearded giant into their order.

In one battle, Banhun Lung slaughtered many Qing soldiers, which saved a great deal of the Tiandihui rebels. But the fate of Heaven can be cruel. After the victory against Qing forces, the giant Banhun's horse stumbled on a rocky path and he fell from the saddle, the giant hit his head, let out a single guttural groan, and died.

The monks and Taoist and rebel soldiers mourned the death of Banhun, but were consoled by the fact that nothing in this world happens without the fate of Heaven.

After the cremation and burial of Banhun, the Taoist hermit and chief of the secret order told his men this:

“Since Banhun Lung's death, I consulted my book of divination, the I Ching. The fate of Heaven is clear: the Qing dynasty still has a destiny to fulfill, and will not soon end. If we try to fight them now, we will only meet the same fate as our beloved Banhun Lung. The best thing for us to do now is to disperse throughout the Middle Kingdom, each to man to their own home in their own province, hiding your name and the intention of our secret order. Quietly you should enlist as many brave men as possible to join the cause. We will remain quiet until the fate of Heaven changes to our favor, and at that time we will restore the Ming and avenge our grievances."

The Tiandihui scattered in every direction and established five lodges, each with secret codes and handshakes.

These lodges would over the centuries spread across the world: the Malay, Siam, Java, Taiwan, the Americas, and beyond.

But even as delightful as this origin story of the secret order of Tiandihui is, I found another knot when exploring the tale. The Tiandihui claims an origin of "immemorial antiquity", since the foundations of the earth were laid by uniting the primordial Yin and Yang forces.

A mystical order, destined to rise and fall through the eons — before and after the kingdoms on earth.

In the year 184 AD, those ancients referenced earlier: Liu-pi, Chang-fi, and Kwan-yu La, had pledged their own secret oaths. In that day, their motto was "Obey heaven and do what's righteous", which still imprints every page of the Tiandihui books.

But this origin story is better left as a mystery. One day I may write about the mysteries of the Tao and the Tiandihui, but for now let’s let this topic rest.

Besides, I have taken us very far off the reservation.

What has happened to the story of Yi Koh Hong, and the Ang-Yi orders in Thailand?

The diversion above with the Shaolin and Qing should be useful for the next knot that I venture to unravel on this page.

The Secret Lodge Takes Root in Siam

The full story of the Tiandihui taking root in Siam spans the reign of several kings. Each of the kings — Rama II, Rama III, Rama IV, Rama V, and Rama VI — treated these Chinese lodges differently, depending on the political and economic mood of the time.

It’s worthy to look at each king’s reign in relation to these secret societies, not only to understand the backstory of Yi Koh Hong, but also because there was plenty of battle and bloodshed as they took root in Siam.

And blood spilled on history’s pages tends to make a subject more savory, don’t you agree?

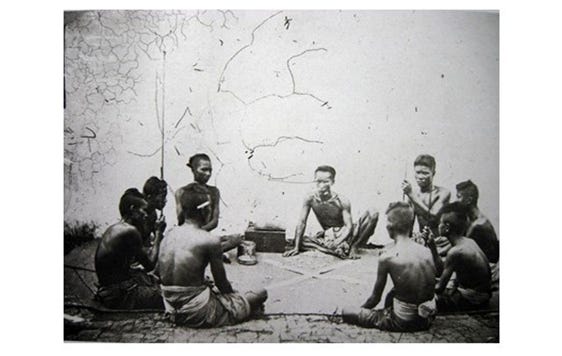

In exploring the knots of Ang-Yi origins, I uncovered an account of the initiation rituals of the Tua Hiya (ตั้วเหี่ย), which was one of the Teochew names that the Ang-Yi were called in Thailand before the reign of Rama V.

This peek into the lodge's rites comes from the royal archives of Rama III:

An oil lantern would first be placed in a bucket of rice, and the bucket sat on a table. Next, a sacrificial chicken was beheaded, its blood mixed with rice liquor and poured into a second bucket. The two leaders of the lodge, the Tua Hiya and the Yi Hiya, held swords over the buckets, forming a sort of arch. Incense sticks burned and initiates would duck under the sword arch, paying respects to their elders. Finally, a cup of the chicken blood and rice liquor was prepared for the initiates. As they drink the blood liquor, the elders holding the two swords warned them: "If you are not honest with each other, your throat will be slashed and blood spilled, like that chicken's that you drink."

Other accounts through time tell of puzzles that must be solved, drinking initiate's blood, and swearing various oaths of secrecy and loyalty.

These lodges, which were all derivatives of the Tiandihui, functioned as labor unions, or mutual aid societies, for Chinese who came to work in Siam and elsewhere. The workers would be offered food on arrival, a place to stay, and leads on jobs. These secret groups were also hotbeds for organizing against the Qing empire back home.

By the time that Rama II reigned (1809 - 1824), British accounts in Singapore noted that Chinese had already settled in Malay. Most of the Hokkien tended to go to Java, the Cantonese to America, the Teochew to Siam, although there were bands of each group in all of these far-flung lands.

It was mainly men who came to establish themselves in the tropics of Siam. They would take up local wives, and after a generation or two of sons following the father's Chinese customs, the line would integrate fully into Thai society. If a Teochew man sired a half-Thai daughter, she would follow the Thai mother's customs from the start.

The southern parts of Thailand, from Phuket Town down the coast to Malay, attracted many Chinese who looked for work. They toiled in the tin mines and harbors. The Tua-Hiya, or Ang-Yi as they were called later under Rama V, took root to support the workers.

When the British brought Indian opium into China, it addicted many men around Chaoshan, the ancestral land of the Teochew. When this group came to Siam, they brought the poppy with them, and this was a factor in addicting Thais. Even nobles in the royal court took to the poppy.

Laws were passed to ban opium, so addicts had to buy and use in secret. Smugglers built up their lucre by bringing in the illicit flower, and the secret lodges of Ang-Yi, who worked the docks in Siam's seaside towns, took advantage of the trade.

Junk ships would arrive from China with the opium mixed in with other products. Ang-Yi dockworkers then sent the product off to be enjoyed in Bangkok’s secret dens.

The trade was so lucrative that the various lodges of Ang-Yi would battle for a leg-up on the hustle. The fighting became so fierce that the royal forces of Siam would have to send in their regiments to squash them.

The first troubles broke out in 1842 in Nakhon Chai Si, which was a province at the time, before being subsumed into Nakhon Pathom. There were no casualties in this flare up.

Two years later, the English set up an opium den between the mouth of the Bang Pakong River and Samut Prakan. Several members of the Ang-Yi were shot dead and the leader of their lodge was captured.

Peace followed until three years later, in 1847, when the Ang-Yi set up an opium den in the Lat Krut (ลัดกรุด) sub-district of Samut Sakhon city. In this battle, 400 Ang-Yi were killed and their leader was captured.

The most violent battle happened the following year in 1848, in the province of Chachoengsao, which became a stronghold for the Ang-Yi. Over 3,000 of the Ang-Yi were left dead from the carnage.

This bloody result did not just happen spontaneously. It was over a year in the making. In 1847, a full year before the 3,000 fell, there was a funeral held for one Mr. Tiang in Chachoengsao.

All of the Chinese in the province heard the news and went to pay their respect at the funeral, which was staged as a traditional Chinese opera by Mr. Tiang's widow.

The group of mourners was led by an Ang-Yi lodge called Siang Thong (เสียงทอง, "golden voice"). On the way to the funeral, the mourners found a bridge that had been destroyed by locals, led by a man named Khwaeng Chan, so that the Chinese could not pass. A fight broke out between the local Thais and the group of mourners, who felt disrespected. One of the elders from the Siang Thong calmed the crowd and the fight ended with no casualties.

A couple of months later, the son of Khwaeng Chan filed a lawsuit with Phraya Wiset Luchai, the mayor of Chachoengsao. He accused the Siang Thong and its members of provoking the fight at the bridge. An order was issued to arrest the 190 members of the Siang Thong, along with 100 others who were in the group of mourners.

But the secret lodge of the Siang Thong could not be found. Instead, a camp of random Chinese laborers, who were unaware of the fight at the bridge, was raided and the men were arrested — at least the authorities had somebody to blame.

The mayor Phraya Wiset Chai used his power to demand a fine from the arrested Chinese. Each person was to pay 5-10 taels (ตำลึง, tamlueng, equal to 4 baht each) of silver, and then could be released — this would have been a half year’s wage, at least, for these poor workers.

Hearing about this news, the Siang Thong stepped up and paid the fine of the innocent Chinese laborers, which cost a total of 4 catty (ชั่ง, chang), or 80 tael, or 320 baht of silver, which would equal 4,878 grams of that precious metal.

This was no small sum. It would be the monthly wages of hundreds of people.

It's without shock that the Siang Thong order was furious. They persuaded the other Yi-Hiya (ยี่เฮีย) — leaders of the other Chinese secret lodges — in the province to join their plan to retaliate. They drew recruits from every language group and order, from Teochew, Hakka, Hokkian, and Hainan stock.

The conspirators laid low for months until they sprung their first offensive.

It all started on the morning of the 7th day of the 5th lunar month in 1848.

The Siang Thong, along with 540 of their recruits, attacked the sugar mill of Zhu Hee. They killed Jean Ho, who was a government official, and elder brother of Zhu Hee.

On the same night, the Siang Thong ordered the city of Chachoengsao to be attacked. Over 1,200 of their recruits stormed the provincial capital. At the time, the mayor Phraya Wiset Chai and his officials were in Krabi. The city was overtaken.

The Ang-Yi set fire to the Royal House of Yok Krabat, the Department of Agriculture, and many residential homes. The leader of the Siang Thong organized a patrol in each corner of the city. Chachoengsao was occupied by the Chinese, who avenged the abuse they suffered under the city's officials.

The next day, the Siang Thong gathered forces and organized to defend the city walls. They brought in 35 cannons and installed them to defend the perimeter. Crews were sent to the sugarcane mills on the outskirts of the city, which gave them an advantage if Siamese forces were to attack.

Enlivened by their victory, the Siang Thong was able to recruit more willing Chinese to their cause.

Many of the Thais living in Chachoengsao fled to the forests. Some took up arms and staged a counter offensive on the Chinese, which was moderately successful. They retook a couple of the sugarcane mills and caused some of the Chinese to flee.

In short order, the government in Bangkok was alerted to this rebellion.

There was only one man who they knew to call on that could squash the uprising at Chachoengsao. A man named Dit Bunnag (ดิศ บุนนาค) — square and honest face, grim eyes, noble countenance like a chief of an American Indian tribe — who descended from the storied and legendary Bunnag family of Mon and Persian races. The patriarch of the family, a merchant from Persia named Sheikh Ahmad, arrived in Ayutthaya in the 16th century. His lineage was involved with Siamese royal affairs for centuries.

Many places around Thailand are named after this family — any place with Somdet Chao Phraya in its name is in honor of this line.

Dit was a trusted man in the Siam court. He was one of three Siamese delegates who took part in the Burney Treaty of 1826 with the British. In 1831 he squashed rebellions in Malay and Pattani. He received personal letters from President Andrew Jackson and helped usher in the Siamese-American Treaty of Amity and Commerce in 1833. And in that same year, Dit led the Siamese fleet to attack Saigon in the wars against Vietnam.

Dit’s son, Chuang Bunnag, would later become the regent for the young King Rama V. But that’s a story for another dispatch.

When the Chinese lodges staged their uprising in Chachoengsao, Dit Bunnag called on a regiment led by Phra Indra Asa, mayor of Phanat Nikhom in Chonburi, to lead the advance into rebel-held city.

The Siamese forces routed some of rebels, forcing them out of the sugarcane mills that they occupied. But the army of Indra Asa was attacked by a skilled group of Chinese led by Long Zhua, forcing the retreat of Indra Asa back to his city of Phanat Nikhom.

The Siang Thong knew what was coming after this first attack. They prepared for the onslaught of the royal army that was soon to arrive. The Chinese dug trenches 400 meters long around the city walls. Weapons were handed out to all of the Ang-Yi brethren, and the Siang Thong prepared to fight to the death.

On the 10th day of the 5th lunar month, a full five days after the occupation of the city, the forces commanded by Dit Bunnag departed from Mahachai (an old name for Samut Sakhon) for Chachoengsao. It took the general’s forces two days to arrive and converge on the occupied city.

In short order, Dit Bunnag's troops were able to subdue the Siang Thong. But the carnage had yet to truly begin.

The Siang Thong knew they were no match for Dit Bunnag and his troops, so they chose to parlay and offered the heads of other Chinese conspirators, who they said were the real culprits behind the occupation. So the Siang Thong captured the leader of a rival lodge to offer to Dit Bunnag.

But the plot to betray their compatriots to save their own hide was too late. On the following day, Dit Bunnag received word from King Rama III that all of the Chinese who were involved with the plot to occupy the city were to be arrested. Dit Bunnag gave the orders and the leaders of each lodge of the Tua-Hiya, or Ang-Yi, were detained — including the Siang Thong.

Reinforcements arrived from Cambodia the next day, which helped Dit Bunnag capture the rebels. The Siang Thong and other Chinese did not go down without a fight. Over the next two weeks they battled with Siamese royal forces, until each of their leaders were captured or killed.

The local Thais who had fled to the forests returned to join the fight against the Chinese.

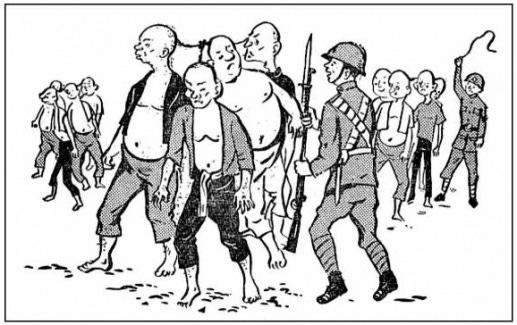

After the dust settled, over 3,000 from the various Ang-Yi lodges were killed. Many escaped. And for those who were captured, they were given the following punishments: the leaders of the rebellion received 100 lashings and then beheaded; those Ang-Yi leaders who did not wage war were given 100 lashings and a life sentence in prison; and those who were even named as associates of these rebels were given 50 lashings and tattoos on their cheeks, which identified them as Ang-Yi.

The imprisoned were released three years later during the reign of King Rama IV. That would be the year of 1851, the same year that Yi Koh Hong was born.

These were the social conditions that Yi Koh Hong was born in. The Chinese were looked at with great suspicion at the time and for the century that followed. They were plotters, conspirators, members of hostile secret lodges who dealt in opium and insurrection — the enemies of King Rama III.

But they were given a second chance by King Rama IV, which we will explore in the next section.

The soil of Siam was fertile for a man like Yi Koh Hong to sprout up in, a man who united the King of Siam and the secret lodges of the Chinese with a single vision.

Gold can smooth any wrinkle, as they say.

The Two Friendly Kings

The wheel of time turns and kings change, and their kingdoms along with them.

The Tua-Hiya, or Ang-Yi, under King Rama III faced difficulty from all sides. After the events at Chachoengsao, things looked bleak for the lodges. They were enemies of the state and anti-Chinese sentiment had taken hold in the kingdom.

Siam was changing rapidly at this time, and after successful wars with Burma and Vietnam, the Thais faced another looming threat: Western colonial powers, who were carving up Indochina and seizing its riches.

King Rama III passed in 1851, having sired 51 children, none of which became heirs to the throne. That honor was given to his half-brother, Mongkut, or King Rama IV, who had spent 27 years in the Sangha, or Buddhist monastic order. He was a mature 47 years of age when he took the throne. Although for a time he gave up the world, when Rama IV entered the palace, he wasted no time in producing heirs. It's said there were 3,000 women in his court, and he took over 30 wives and sired over 80 children, one of which was Chulalongkorn, the man who would later become King Rama V.

We will return to Rama V a bit later on.

The man who had advocated for Mongkut to ascend as king of Siam the most was none other than Dit Bunnag — and in a rhyme of fate, it was Dit Bunnag’s own son, Chuang, who later secured the throne for Mongkut’s son, Chulalongkorn — who had wrestled the city of Chachoengsao back from the rebel Ang-Yi. This solidified the Bunnag line as the most powerful noble family in the kingdom. Political power rested in the hands of Dit Bunnag and his brother Tat, who was appointed as the king's regent in Bangkok.

King Rama IV is known for his opening up of Siam to Western ideas, culture, and social reforms. He is none other than the king from the King and I, a story that I'm confident you're well acquainted with.

The Chinese secret societies, who dominated the opium trade in Siam, faced hardship under Rama III. But when Rama IV took the throne, he changed his stance on the Tua-Hiya and their illicit trade. The king knew it was impossible to squash out the import and sale of opium completely, so the choice was made to monopolize the trade. The government became the only party authorized to buy and process opium for sale. The Chinese were allowed to use the poppy, but Thais were forbidden to touch the stuff.

There were Chinese scattered across the kingdom in every province, especially in the southern lands, and Rama IV knew that it would be wise to deal with them in a civil manner. The king set up a position of a Permanent Secretary of China in the Department of Civil Affairs in each province that had a sizable Chinese population. The role was intended to support the livelihood of Chinese workers, which was a way to smooth over the conflicts between Siam and the Chinese who lived there.

Intentions were good between Rama IV and the Tua-Hiya. He implemented a policy called "Raising the Ang-Yi" (เลี้ยงอั้งยี่), which was modeled on the British policy towards the Chinese secret lodges in Malay and Singapore.

At the time, there were more foreigners of Chinese descent in Siam than all the combined western nations. They were known as "those under the flags of foreign countries" (อยู่ในร่มธงของต่างประเทศ), and they did not have to obey the jurisdiction of Siamese courts.

The concern was that the Chinese would defect to the banner of western nations. The solution was to establish a sort of Chinese court within Siam, which would settle cases and mete out judgements in their communities. Chinese language and traditions would be used for civil matters. Every district that had a sizable population of Chinese would have their own sheriff, who would report to officials in the royal court.

This was very effective in keeping the peace with the Ang-Yi, as the numbers of Chinese swelled in the kingdom.

As the king opened up economic relations with the Western powers, especially with the Bowring Treaty of 1855 with Britain, there was a new economic boom in the kingdom. A sudden and sharp need for labor in Siam arose, and as the majority of Thais were either classed as Phrai (ไพร่, indentured workers) or That (ทาส, slaves), and were tied to a noble's land, movement of labor to where it was needed most in saw mills, tin mines, and rice mills was realized by the Chinese who flooded in from Chaoshan.

Workers themselves became a commodity. And as the Tua-Hiya in Siam maintained contact with their compatriots back in China, they could recruit workers to come to Siam and arrange their transport and welcome.

More junk boats were sailing the route between the ports of the two countries. The arrival point for the Chinese in Siam was Bangkok, and the Tua-Hiya settled many of the new arrivals in the burgeoning city.

But many of the Chinese and their lodges were in the south, especially in Phuket. The Chinese lodges in Singapore saw the opportunity in Siam and they wanted in on smuggling workers to the kingdom. This stepped on the toes of local Chinese lodges who had lived and operated in Siam for decades already.

For the majority of King Rama IV's reign, the peace was kept with the Chinese lodges in Siam up until 1867, the second to last year of his rule. One group of Ang-Yi from British Malay, and the other in Phuket, fought over a water source that was used in tin mining operations.

The two groups of Ang-Yi had 3,500 and 4,000 members respectively. A fight broke out between them in the middle of Phuket Town. The mayor tried to negotiate terms between the two rival Ang-Yi lodges. Leaders of the cartels were brought to Bangkok to settle their disputes in front of the king. They drunk a "holy water" and swore an oath to remain peaceful while they lived and worked in Siam.

In this ceremony, 14 of the Ang-Yi chiefs were brought to Wat Kalayanamit Woramahawihan (วัดกัลยาณมิตร วรมหาวิหาร) in Thonburi, a temple that the Chinese revered, and swore to not harm the king and to keep their minions in order.

King Rama IV's policy of "Raising Ang-Yi" seemed to work. The fighting in Phuket was calmed during his reign. Just like the British did in Malay, the king received the head of the Ang-Yi lodges and gave consideration to their concerns and grievances. If the Ang-Yi had a problem, Rama IV listened.

This policy implicitly sanctioned the Ang-Yi's activities in Siam as long as they didn't do damage to the kingdom. The secret lodges thrived in this era and became more integrated into Siamese society.

Siamese officials tapped into the power that the bosses of the Ang-Yi held. Law enforcement officers collaborated with the bosses to keep peace within the Chinese communities in Siam.

It was a win-win arrangement. The officials were paid off with tea money from the operation of illicit businesses, like gambling, opium dens, and brothels. Liquor and lottery also became lucrative endeavors of the Ang-Yi and deals were worked out in the royal court with the Chinese lodges so that they could spearhead the industries in Siam.

In 1867, Yi Koh Hong had been in China for two years, and his stint in the last battles of the Taiping Rebellion ended with him joining the Tiandihui at the age of 16. The leader of the secret society was a former Taiping army general and fugitive called Lin Mang (林蟒).

Lin Mang escaped to Bangkok and established the Siam order of the Tiandihui and became its leader for the next twenty years. It was Lin Mang who Yi Koh Hong followed after the battle in Dabu county back when he was a teen.

It's said that Yi Koh Hong worked hard in his youth and earned the respect of the Ang-Yi. From the harbor to the streets of Sampeng, and north to Chiang Mai, his name was respected in the land of Siam.

The connection to Chiang Mai and the border regions of northern Thailand and Burma seems to pop up in several Chinese language accounts of Yi Koh Hong’s life. It’s a point that I’d like to explore further, but haven’t tracked down more details about what happened here — if you have any leads, let me know.

Not many details are known about Yi Koh Hong's activities in the last year of King Rama IV's reign, but it can be deduced that the young man was building connections and respect with his countrymen and the Siamese alike.

His fortunes would soon change drastically, birthing a legacy that lives to this day.

In the meantime, King Rama IV and his son Chulalongkorn ventured to the Malay Peninsula to witness the solar eclipse in August of 1868, which was calculated by Rama IV. Both the king and his son the prince contracted malaria while on the journey, and Rama IV passed away in October of that year.

Chulalongkorn was only 15 years old when his father the king passed. It wasn't a guarantee that the prince would survive the bout with malaria, and so the question of who would inherit the throne was at the top of Rama IV's mind before he passed. He wrote on his deathbed that "My brother, my son, my grandson, whoever all of you senior officials think will be able to save our country should succeed my throne, choose at your own will."

The son of Dit Bunnag, Chuang Bunnag, managed to secure the throne for the young prince Chulalongkorn and on November 11th, 1868, the coronation was held and the prince became King Rama V. Chuang was his regent for several years as the young king learned the ropes.

Chuang Bunnag also oversaw the affairs of the Ang-Yi in Siam. He ensured that the Ang-Yi paid their tax on their business dealings, whether illicit or kosher, and smoothed over tensions and rivalries between the lodges.

There were a few incidents involving the Ang-Yi in the beginning of Rama V's reign that stand out.

In 1873, there was an Ang-Yi order that wanted in on the opium dens on the banks of the Chao Phraya in Samphanthawong district. A group of young upstarts attacked another group of elder Ang-Yi stationed in Nakhon Chai Si. Chuang Bunnag punished the leader of the young gang by executing him and his followers were imprisoned.

Chuang Bunnag used the oldest tactic known to man to keep the Ang-Yi in line: fear.

The regent would organize military field practice near the Grand Palace. This involved soldiers firing rifles that would deafen those watching.

Even more frightening, the field marshal would set out human-like figures stuffed with hay on the training grounds. War elephants would be let loose on the figures, stampeding over them. The figures looked very real and everybody in the city, especially around Chinatown, saw and felt the destructive power of the Siam royal army.

But the Chinese in the southern provinces, like Phuket and Ranong, proved difficult to control.

There's a series of incidents in the southern provinces that have captured the attention of those interested in the history of those lands.

It started in 1876, the Chinese year of the Rat, and the 9th year of the reign of King Rama V. The Chinese tin miners in Ranong and Phuket started to raise hell about taxes, the plummeting of the price of tin, and other oppression.

The Ang-Yi behind these rebellions were known as the Ash Cement Cartel (กงสีปูนเถ้าก๋ง). They were an Ang-Yi branch from British controlled Malay, not from Bangkok, and they had no connection with the Ang-Yi lodges in Siam's capital.

At this time, there were more Chinese in Phuket than there were Thais. Tens of thousands of workers toiled in the Phuket tin mines. The majority of the workers were loyal to the Ash Cement Cartel, the lodge that had brought them to Siam to work from Chaoshan.

The same thing happened in Ranong. As the price of tin collapsed, the workers couldn't get paid. During the Chinese New Year, a fight broke out over the economic crisis, and several people were killed. Hundreds of tin miners fled from arrest over the incident. Most landed in Phuket for refuge.

Things were hairy in Phuket. The number of Chinese workers were multiple times more than Ranong. If things went pear-shaped with them, all hell would break loose.

The governor of Phuket at this time, Phraya Wichit Songkhram, was tasked to rule the resource-rich island and collect and manage its taxes. The Chinese grew to despise this man.

One afternoon, a warship of Siamese sailors landed in Phuket. They went to drink in Phuket Town and were looking for trouble. Soon enough they got what they were looking for. A fight broke out between the sailors and the Chinese workers local to Phuket. A command was issued for the sailors to return to their ship, but two of then snuck out at dusk to finish what they had started.

When the Chinese saw the two sailors, they swarmed him and beat them to death. One of these Chinese culprits was brought to Phraya Wichit for punishment.

The Ang-Yi were livid.

Around 300 Chinese gathered in the market after the arrest. They carried melee weapons and torches and stomped through town. They attacked the police station, temples, and homes of Thais in the city.

The local Thais were outnumbered and fled for survival.

The Ang-Yi called in 2,000 more workers. Their goal now was to raid the mansion of governor Phraya Wichit Songkhram. The governor was able to evacuate with his family and escape to safety

You can still take a tour of Phrayta Wichit Songkhram's mansion, or what remains of it. The home is located on Ban Tha Ruea Thepkrasattri Road, Si Sunthon Subdistrict, Thalang District, Phuket.

Phraya Wichit called on the sheriff to release all Thai prisoners from the jail, which numbered about 100, to fight off the Chinese. The sailors, which were another 100, were also called back onto land. Each were armed and set up artillery on every road to fire on the Chinese on sight.

The leaders of every Ang-Yi lodge were summoned to the town hall. They were given instructions to hand out fines for the villains in their own clans, and to patrol the city for any trouble. The feelings were split and the Ang-Yi chiefs could not control the violence.

A dispatch was sent out by telegram to Penang to tell the British governor to stop all weapons from leaving, as they would be sent to the hands of the Ang-Yi in Phuket.

The town hall in Phuket Town was protected but the Ang-Yi rebels in the city and countryside continued their rampage. Thai houses were burned and pillaged in the riots.

An urgent telegram was sent to Bangkok requesting reinforcements. Chuang Bunnag set off with Thai and Malay battalions, which were able to squash the 1876 rebellion in Phuket.

An agreement was made that only those who killed or plundered in the riots would face punishment. The normal workers would be blameless as long as they apologized for their actions — that was their only penance. Many of the Ang-Yi leaders who staged the riots fled to British-held territories throughout Malay.

The legacy of these secret Chinese lodges survives in Phuket through strange ways.

You may have seen the curious photos that come out of Phuket’s annual Vegetarian Festival (งานประเพณีถือศีลกินผัก). This celebration likely originates in Ang-Yi and Tiandihui organizing.

The Chinese lodges in Hokkien province started this annual ritual. They were heavily anti-Qing and used the festival as a point of organizing fellow recruits through acts of penance. The lodges in Hokkien were snuffed out but as many of them fled overseas the traditions continued. One of the most important traditions they carried with them was this festival, and thus it became very important in Siam and Malay, even more so than in China.

Of course, one of the songs of this festival is the old refrain, “Overthrow the Qing, return the Ming” (โค่นชิงฟื้น หมิง in Thai).

There were other incidents in the southern provinces that came to pass under Rama V.