New Lords of Asia: Zhao Wei

There is a thin line between a fool and a great man. Allow me to properly introduce Zhao Wei.

“How do you remove the mountain? It is impossible, you fool!”

“Although I can’t move it and I will die, there will be sons and grandchildren; and more sons and grandchildren; and more sons, and more sons. There is no limit. And since the mountain never grows taller, piece by piece, they will conquer it.”

— The Foolish Old Man Removes the Mountains (愚公移山), 5th century BC, from the Daoist text Liezi (列子)

Important Note: The email you receive for this dispatch may not display in full due to its length. You can read the full version by clicking the button below:

Dear expats and readers,

There are new lords in Asia.

Who measure their impact not just by the spoils and lucre from their commerce — of which there is plenty, both sanctioned and criminal alike — but by their hand in shaping a destiny that will span decades and centuries into the future, whether they are conscious of that fact or not.

These men stand as titans, unmoored from the heavy ethical burdens that stop you or I from seizing their level of power.

Because that is what I am writing about — a new kind of power, unique to the 21st century and Asia, that the limitations of Western law and tactics can’t possibly bring down.

Some of these new lords are known by name. And in this dispatch, we look at Zhao Wei — a name that may ring familiar to some of my readers, as he often shows up in lazy write-ups in Anglophone rags like Vice and CNN, who have painted him as a caricature of crime and evil on the Mekong.

Don’t read me wrong — I am not coming to Zhao Wei’s defense here.

But over the past year I’ve put considerable thought into a question that has wormed its way into my brain, and over time only burrows further: that is, “Who is this Zhao Wei?”

There are two ways to look at this question.

The first is to know him through the headlines: the U.S. Treasury sanctions against him, his businesses, and associates, deeming him a kingpin in a transnational crime organization (TCO); the wildlife, narcotics, and human trafficking; the murky connections to the Mekong River Massacre of 2011; his association with figures like the rebel leaders Sai Leun of the Shan and Wei Hsueh-kang of the Wa — both major narcotics smugglers, both notably despised by the U.S. State Department.

There is another way to know Zhao Wei. But it takes more work — both in a literal sense of seeking out non-English language sources, which takes time and a great deal of patience. And in another sense that is more difficult still: to ask better questions about who Zhao Wei really is.

If what he was doing was as simple as pushing meth down the Mekong, or laundering money in his Kings Romans casino, then I wouldn’t have spent much time on this case.

I wouldn’t have combed through hundreds of sources, documents, and interviews — each leading to new questions, unearthing more tendrils of power, that spiral out from Hong Kong to Macau; Mong La, Myanmar to Chiang Rai, Thailand; Beijing to Bokeo, Laos to Parchim, Germany — yes, even to the fatherland.

Before we get to the meaty bits that I’ve hunted down, bagged, cured, and prepared for your reading pleasure, I want to be clear on a few things.

I’m not a journalist. I have no credentials — and I’m far from an expert in any sense of the word.

When I write about the subject of organized crime in Asia, I do so as somebody, much like yourself, with a vested interest in the matter — whether that’s because you travel to the region, or you live here and set down roots, and have developed a curiosity in these things.

It’s my intention to tell things as they are — neither romanticized, nor understated — nothing more, nothing less.

I can promise you one thing, though — before I put out any dispatch, I remove the blinders that may obscure the subject at hand. I only ask that you do the same when reading what follows.

I have my own unique process when doing research for a story. I’d hate to show you all of the notes, spreadsheets, screenshots, and photos that I save when stitching together a dispatch like this — it’d give you a feeling of confusion and anxiety more than cohesion or clarity.

But I will show you anyway.

I make frequent use of hyperlinks throughout this story and I will include a spreadsheet of all of them at the end. If you’d like to know where I source certain information, click the hyperlinks, but many of them will take you to material in Thai, Lao, or Chinese.

In the text itself I also include the Thai, Lao, or Chinese names of people, places, and businesses in parentheses where relevant; this is important for others who may want to use them and do additional research, as mostly the names in the original tongues are not transcribed in the Anglophone rags.

The central character in this dispatch, Zhao Wei, presented another unique difficulty during the research stage.

Zhao Wei is a Chinese national. This fact obscures biographical and business dealings behind a veil of language and culture that is rarely translated, and often remains inaccessible — relatively speaking. It’s much easier to trace the financial and personal background of an American or German, for example: language is more accessible, records are more transparent.

Most of the Anglophone press on Zhao Wei is regurgitated from a few sources, which are rehashed from time to time by rags — both minor and major — when they need a story to run to fill up digital space.

Very rarely are primary sources shown to readers of these articles that are churned out about men like Zhao Wei, although they are eluded to often — business registrations, handshakes with political leaders, state sanctions.

I find that disrespectful in two ways: to the reader for not giving them the ability to trace information back to its original source, which is annoying and insulting to the reader’s intelligence both; and disrespectful to the character of Zhao Wei himself, who, as I have learned more about him, strikes me as a character with depth and complexity, and not a headline caricature — that is, he is a much more complicated and three-dimensional figure than what has been largely written about him.

One of my goals will be to reveal as many primary sources about Zhao Wei and his dealings that I can, because I respect your intelligence as a reader, and I respect the unlikely path that Zhao Wei has taken to his seat of power.

A note: I will lay out Zhao Wei’s life and dealings in a relatively chronological fashion.

Without further ado, let us meet Zhao Wei.

An Unlikely King

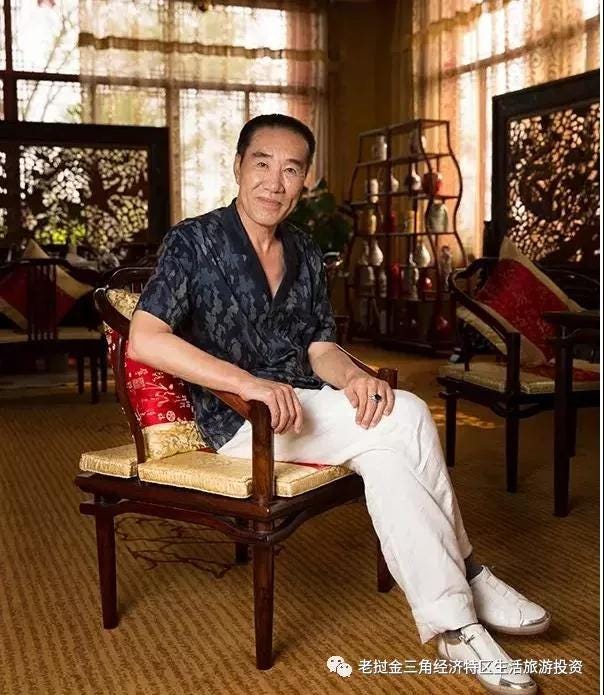

Zhao Wei (趙偉 in Chinese) comes from humble beginnings.

He was born on September 16th, 1952, in rural Heilongjiang Province (although the US Treasury Department, when issuing sanctions against Zhao Wei and his accomplices and enterprises, says that he may have been born in Liaoning Province; this is also mentioned in a variety of secondary sources, but in interviews, Zhao Wei says Heilongjiang) — which is nestled in the most northeasterly corner of the country, snug against Russia’s far-flung Amur Oblast federal region.

A cold place with a hearty people.

His early biography is apocryphal and spotty — and is known mainly from confessions in interviews with Chinese state-run media, many which came after the Mekong River Massacre. Damage control, you could say, and a subject we will explore later on.

He was born into poverty. He endured the Cultural Revolution.

He has said that his family was so poor as a child that books were a luxury — but one was leant to him by a neighbor, a volume by the Song Dynasty poet Wen Tianxiang (文天祥), which had a special influence on his life.

Zhao Wei often quotes a specific, proverbial line from a poem in this volume titled Crossing Ling Ding Yang (过零丁洋), written in December 1278 —

Who has never died since ancient times? Keep your loyalty and your history. (人生自古谁无死,留取丹心照汗青)

— the import being that people will inevitably die, but they must be worthy of history before they do.

This is how Zhao Wei views himself. He is shaping the course of history for China in the Golden Triangle. He is the Old Fool from the Daoist fable quoted at top of this dispatch, who may not move the mountain himself, but who is the first in a line of many who will — all of this work for the greater glory of China and its history, an admission made in this interview, which also happens to reference Chairman Mao, who also included this bit of Chinese myth in The Little Red Book.

There is a deeper layer to the poem Crossing Ling Ding Yang as it relates to Zhao Wei’s life.

The poem was written as Wen Tiangxiang witnessed a losing battle between the Chinese Song forces and the Mongolian Yuan near the river Ling Ding Yang — the middle channel of the Pearl River, emptying into the Pearl River Delta — the body of water between Hong Kong and Macau.

This was where the poet saw the bold fight against imperial Mongolian occupiers, and it’s where Zhao Wei, seven centuries later, became a made-man.

It’s in the early 1990s, in Macau, where Zhao Wei broke free from provincial toil — he harvested and engaged in a small timber trade in Heilongjiang — and built wealth and connections that served him well in the years that followed.

He built a small fortune in Macau in the casino business, although details about his dealings here are scant — I’ve searched for many hours to find what casinos he was involved with in these early years, and have come up empty-handed. Although there is a reference to Zhao Wei losing millions of yuan in chips at a Macau Sands Casino after the U.S. Treasury issued sanctions against his enterprise.

In interviews he has said that he was making more money than he could spend, more money every day, although it’s clear, by his own admissions, he didn’t own a casino — as the capital requirements were beyond his means, and he wasn’t well-connected enough at that time.

And yet, these were heady times for Zhao Wei in Macau, as he reveled in the sudden wealth — which was spent as quick as it came.

The highs and lows were extreme. His business went bust and with debts and pressures mounting, he fell into a six month depression where he would "lay in bed and look at the ceiling every day."

It’s at this low ebb when his eldest daughter fell ill with cancer. Zhao Wei ponied up 500,000 yuan for her to see a doctor in Beijing — and she presumably pulled through.

His wife, Guiqin Su (蘇桂琴), pulled Zhao Wei through this difficult time, providing an unwavering spousal support that still earns Zhao Wei’s respect to this day.

Zhao Wei got a taste of casino lucre in Macau, and this became a main feature in the years that followed.

It’s an unknown why he left Macau, or how much capital he had — although we know he did build up a handsome network of investors that followed him.

Zhao Wei chose a daring territory for his next move, a risky but profitable leap.

The Move to Mong La

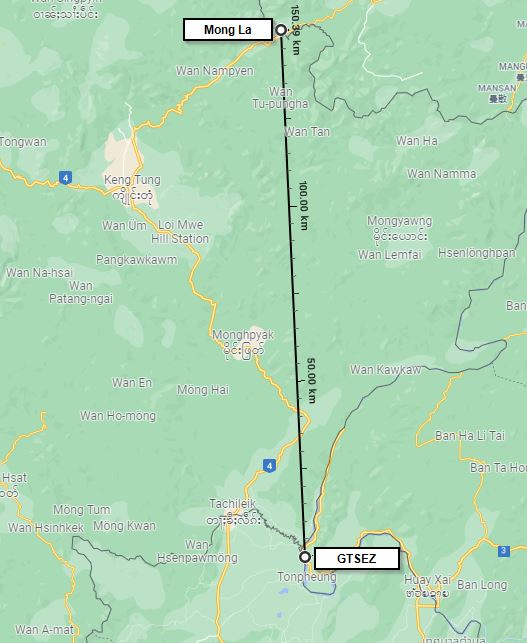

Zhao Wei’s first move was to Mong La, Myanmar — also known as Shan State Special Region 4, an autonomous zone ruled not by the Burmese central government, but by a faction of the Shan army. This would have been around 2001.

It’s there that Zhao Wei founded a hotel and casino complex — one of the leading four in the city — called by various names throughout its existence: Blue Shield Entertainment (蓝盾娱乐), The London Casino, and the Grand London Hotel. I’ll get to why the names changed shortly.

Blue Shield Entertainment was a hotel and casino complex kickstarted with a 300 million yuan investment (roughly $37 million USD at the time; for all figures quoted in yuan in this section, the rate was roughly 8 yuan to 1 USD at this time) and was owned and operated by a Macau company called Macau Blue Shield Group (Myanmar) Co., Ltd. (澳门蓝盾集团(缅甸)股份有限). It’s clear from this that Zhao Wei had flush connections back in Macau who helped get this operation off the ground in Mong La.

In fact, retirees from the Macau Gaming Inspection and Coordination Bureau were invited to Mong La as salaried directors of the Blue Shield Entertainment company. The identities of those retired bureaucrats is unknown, although with the right resources, I could probably comb through and suss out who they were.

Blue Shield wasn’t just a casino, though.

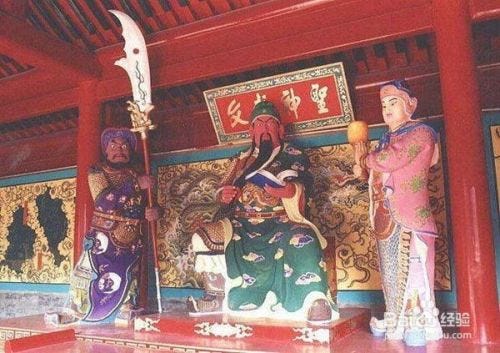

Even early on, Zhao Wei had higher ambitions of establishing a leisure and cultural footprint. The company built a golf course and a temple dedicated to the Han dynasty general Guan Yu (關羽), who is reverentially called the Emperor Guan (Guandi, 關帝) or the Lord Guan (Guangong, 關公).

This tendency to build out legitimate cultural, leisure, and tourist attractions alongside gambling operations is a feature of Zhao Wei’s business strategy even after leaving Mong La, and becomes an important part of his story in the following chapters.

On June 16th, 2001, a magazine called Starlight News — a local Mong La rag that covered the happenings around town — devoted a large amount of space to the ribbon-cutting ceremony of the Blue Shield International Hotel, the Mong La golf course, the Mong La Jewelry and Jade Exhibition Hall, the opening ceremony of the Mong La Business Center, along with the opening of the Mong La Shrine and Golden Pagoda, all of this debuting on the same day, May 15th 2001.

The reason for this day? Nothing in particular, except that Lin Mingxian (Chinese: 吴再林, Burmese: စိုင်းလင်း), also known as Sai Leun, happened to come to Mong La for inspections on that day.

A brief diversion: Sai Leun is an important figure to this story, and is a man with a long, complicated influence on this region of Myanmar. He is the chairman of the Shan rebel group, the National Democratic Alliance Army (NDAA), and de facto leader of Shan State Special Region 4, which contains Mong La and surrounding land. He was tasked by central Burmese authorities to rid the region of opium.

That didn’t quite happen, of course. What did happen was Sai Leun built up a substantial narcotics fiefdom, along with courting Chinese investors and entrepreneurs to build up Mong La as a casino paradise in 1998 — which was after the April 1997 announcement from the central government of Myanmar that this zone had been completely cleared of narcotics.

For a deeper look at Sai Leun and this region of Burma, which exceeds the scope of this dispatch, please refer to the legendary and astute journalist Bertil Lintner’s work here, here, and here.

It is clear that Zhao Wei and Sai Leun must have known each other, as they would have been present together at the ribbon-cutting ceremonies in May 2001, which launched a variety of important business and cultural ventures in Mong La. And as one of the major casino operators, Zhao Wei would have in the course of his business there dealt with Sai Leun, leader of the zone.

It’s unclear how well the two knew each other, or if they remained friends after Zhao Wei left Mong La, but there is speculation that Sai Leun did invest in Zhao Wei’s later enterprises — again, more on this in a later chapter.

The benefit of these casinos operating in Sai Leun’s fiefdom was clear — he was raking in millions of yuan from taxes paid by the casinos, along with the added benefit of hundreds of thousands of Chinese tourists crossing the border to splash cash, as gambling remained illegal at casinos in the Mainland.

Investments in local infrastructure included 10 million yuan in roads and bridges for local farmers, 20 million yuan for the welfare of locals, and the exemption of all taxes and fees for farmers in the region.

By the summer of 2003, investments in Mong La from China, Hong Kong, and Macau had reached nearly 5 billion yuan, and gamblers had lost over 40 billion yuan in its casinos.

Blue Shield and the other casinos in Mong La were clever in the ways they made their money.

During the Spring Festival of 2002, the Blue Shield Casino held a contest called the "Gambling King", where players would pony up 20,000 yuan to participate, and winners would be rewarded with 800,000.

The Blue Shield Casino would also ensure the safety of participants by sending armed escorts to ferry the gamblers from the Chinese border to the property and back. Safety was a concern at this time, as even as early as 2001 reports were leaking to punters in the Mainland that kidnappings, extortions, and even disappearances of gamblers in Mong La were becoming common.

Some of these kidnappings were conducted by both Burmese and Chinese loan shark gangs, who took root in Mong La, and were more than willing to lend to gambling addicts at the tables. These loan sharks would spend upwards of 18 hours a day surfing around the casino floors, feeding advice to freshly arrived gamblers, waiting for them to lose it all, and then swoop in to offer loans so that they could keep rolling the dice and flipping cards.

These VIP halls would be contracted out to operators from various regions in Mainland China, who would market to and source customers from their own provinces. The VIP halls would rent for no less than 20 million yuan.

One casino had 11 VIP halls, each with more than 100 gaming tables. The tables would be rented out to other subcontractors at a rate between 4,000 and 6,000 yuan daily, with annual sums totaling up to 180 million yuan.

The operators would also take a 5% draw on gambler winnings.

I have never been to Mong La, but I have been to Las Vegas too many times to count, and even there an air of desperation and misery can be felt — I vividly recall seeing weary gamblers who lost their shirts begging with cardboard signs off Fremont Street, asking for just enough cash to get home.

In the Vegas of the East, as Mong La was dubbed in its halcyon days, this same climate of loss and misery descended on the city, as Chinese gamblers flocked in to test their luck. Suicides were common. So were the disappearances.

Stories of gamblers ending up buried alive in the surrounding Burmese hills were common. The loan sharks did not play games in Mong La, and the lawlessness of the area was renown.

A type of recruitment scheme also took root. Unscrupulous players indebted to loan sharks would farm their contacts back in the Mainland for anybody willing to travel to Mong La to experience the excitement and allure.

The recruiters would earn a cut, ranging between 10-15%, of the newly arrived gambler’s losses — and these could be substantial.

A legend sprang up about a heroic gambler by the name of Liao Wang (廖王), who became known as King Liao, or affectionately, Brother Liao.

Some said he lost more than 400 million yuan in Mong La. He was reportedly a native of Sichuan and had extensive business there. He was one of the first to come to Mong La from China and opened a restaurant.

He was known for his generosity. When he won, he'd give players at the table 10,000 yuan for good luck. He was well-respected by other gamblers.

Other stories circulated. One involved a gentleman from Yunnan, who patiently watched the betting habits of others at the tables. He helped gamblers with big pockets at the tables, giving them advice on how to edge out the house odds. After one substantial victory, he was gifted 20,000 yuan as a reward, and later turned that to 4 million yuan — and then gave up gambling entirely.

Recruiters used these tall tales of fortune and luck to lure punters to the Mong La casinos.

This is all to say that business for Zhao Wei, the Blue Shields Casino, and Mong La was booming. These were the golden years of this border town, where the intense demand from Chinese gamblers gave rise to a city like a mirage from a once desolate, undeveloped zone of jungle and hills.

That all changed in 2003.

The daughter of a high-ranking official lost 1.4 million yuan at a Mong La casino. She was recruited by a good friend of hers, who received that 15% cut on the losses.

The daughter's family reported the case to Beijing, and officials from Beijing sent investigators to Yunnan, the province that borders Mong La.

What they found was shocking. A bank in Xishuangbanna Prefecture was used to send tens of billions of yuan to Mong La illegally each year. After combing through the transactions, the Beijing investigators found that various provincial officials throughout China had gambled away millions of public funds at the Mong La casinos.

They also found proof that hundreds of Chinese citizens had disappeared after venturing into Mong La — their whereabouts still unknown.

On July 11th, 2003, the Chinese military conducted an operation called Blue Arrow (蓝箭) and seized the property and businesses of the five largest casino operators in the border town. The raid came as a surprise. One of the targets? Blue Shield Casino, Zhao Wei's own.

The Chinese government ordered all of the Chinese nationals working in Mong La to return to the Mainland before August 31st, 2003.

The silver lining? That daughter of the official who lost her 1.4 million yuan had it returned by the casinos.

The raids had a chilling effect on casino and tourist operations — Mainlanders could still make it to Mong La, but at a price and with great difficulty. But the operators were clever, and there was simply too much money on the table to walk away from it completely.

Two things happened after operation Blue Arrow.

First, Sai Leun, leader of Mong La, allowed casinos to move about sixteen miles south to Wan Me-Hsiao. The casinos tapped into the burgeoning online gambling space — and profits continued to roll in.

Back in Mong La, many of the casinos flopped — but two were allowed to continue by special order of the Chinese government, one of them being Blue Shield.

They did change their name, though. The company dabbled in a bit of word-play when choosing their new name.

Blue Shield in Chinese is pronounced Lan-dun (蓝盾), which is a name used in various Chinese companies and on a street in Macau itself, where I’d bet Zhao Wei once walked. After the raids, the company rebranded as The London Hotel (伦敦大酒店) — after the UK capital — which was a clever play on the way Lan-dun sounded similar to London.

As an aside, and as something I will bring up in more detail in a further section, Zhao Wei currently operates another Blue Shield Casino — not in Mong La, but rather in Bokeo, Laos, in what is now known as the Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone. I will take you there soon.

For now, I want to take a moment and dig a bit deeper on Mong La.

This dreamy, vice-laced city was more than a gambler’s paradise. It was a place where 90% of the visitors were men who could indulge their every whim and desire — for a price.

One visitor to the Blue Shield Casino's on-site restaurant indulged in a dinner, and the menu was described as "extremely rich, with the delicacies of the mountain and the sea".

Everything was available: salmon, muntjacs, pangolin.

In the markets at the center of the city, shops, restaurants, and open-air stalls traded in tiger skin, talon, and meat, tiger bone-wine, and Asian black bear.

Any sort of sex was on the menu, too.

The prices were printed boldly on business cards and menus for any desire to be sated.

Young American women, young Sichuan girls, Hunan sisters, Russians, gentle and affectionate lovers — male ore female — along with new arrivals, fresh meat, were advertised.

The prices varied: a young Hunan girl would be 200 yuan (roughly $30 dollars at the time), they could come as a pair of sisters for 400 yuan; a Russian girl would cost 300; a gigolo would cost 400; and a virgin girl 4,000 yuan.

Some gamblers paid up to 10,000 for a girl's virginity, as there was a saying that passed the lips of those chasing fortunes at the tables: "opening a virgin brings the best luck."

It’s very unlikely that you will ever go to Mong La. It is now a very difficult place to enter on several accounts: the war, the pandemic, and even before both of those calamities, non-Chinese foreigners who wanted to go to Mong La would have to go from Mae Sai, Thailand, cross over to Tachileik, Myanmar, take transport to Keng Tung, and then hire private escort to Mong La — the last leg of that journey being the most difficult, with spotty stories of success.

In lieu of going to Mong La to breathe in the full bouquet of vice, you can see what it’s like there on the ground in videos.

There is a Chinese site, similar to YouTube, that has many uploads from Mong La.

It’s said that the bulk of ladies of the night in Mong La are Chinese nationals, and there is plenty of them still there.

These are photos from Mong La just before Covid.

Still a busy town, still trading in vice — sex, gambling, exotic wildlife, narcotics — but at a slower pace than the glory days, when Zhao Wei and the Blue Shield Casino operated with all pistons firing.

Although the Mong La gambling revenue likely fell after operation Blue Arrow, it never dried up completely. And although the Blue Shield Casino rebranded as the London Hotel, and later as the Grand London Hotel, and likely involved itself in online gambling as a service for Mainlanders who couldn’t — or wouldn’t, out of fear — make the trip to Mong La to try their luck at the tables, it’s unclear if Zhao Wei exited his position and stake in these operations.

It’s a question with no clear answer.

Did he sell off his shares?

Is he still involved with operations in Mong La?

At the end of the day, we don’t know.

What we do know is that not long after Mong La started its decline, Zhao Wei made a new opportunity for himself and investors that followed him.

Where? On the eastern banks of the Mekong River, on a 100 square kilometer plot of land, in the Bokeo province of Laos, leased for 99 years, about 150 kilometers due south from Mong La.

Its name?

The Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone (GTSEZ hereafter).

It’s at the GTSEZ where the next chapter of Zhao Wei’s story unfolds.

And it’s where things get a whole lot more interesting.

The Mysterious Golden Triangle: Part 2 of the New Lords of Asia: Zhao Wei story

The next dispatch will take us to Bokeo province in Laos, where Zhao Wei and his company, the Kings Romans group, have a 99 year lease on 10,000 hectares of land.

And it’s not just for a casino — it’s a full-fledged settlement outpost, riding on the winds of the Belt and Road Initiative, with highways, an international airport and shipping port in the works, and 30,000 residents.

I’ll take you to the Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone and detail what is happening there from public sources, documents, and Chinese language media.

What I have found has not been covered in the Anglophone press.

The story starts in 2007, when Zhao Wei first broke ground on the project, through 2011 and the incident that shook Mainland China to its core — The Mekong River Massacre, along with Zhao Wei’s connections to that event.

It continues through 2018 when the US Treasury Department levied sanctions on Zhao Wei, his companies, and associates.

But this is only the beginning. As I did research on this story, I stumbled across a link between one of Zhao Wei’s business partners — actually, a company who invested in the GTSEZ — who also bought an international airport in Germany.

This is where the story gets very strange and even surprised me.

Full details on everything to do with the Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone and what’s really going on there in the next dispatch.

Until then,

TCT

If you enjoyed this dispatch, share it with a friend. It’s easy, just click the button below:

Special Note: For this week, I didn’t put out an email for part 3 of the Wheels of Death series — which is a serialized novel project I am putting out — as I don’t want to clog your inboxes. You can expect part 3 this Sunday.